In The Blood

James Patrick, Director of Intelligence at the Cold Case Foundation

As I write and produce the Out Of The Cold podcast, I am also researching and writing a follow-up book on the subject of the series: serial killer Robert Ben Rhoades. This brings with it challenges and complexities. One such area is DNA. Testing can be seen as controversial, and potentially in conflict with Fourth Amendment rights in America, where discussions circle around whether it should one day become mandatory. And that is why context matters, as does looking at issues from a standpoint which is far removed from politics.

The context about DNA in this discussion, about what’s in the blood and why it matters – which started in the latest episode of After The Cold – starts in a field in Texas, in the 1980s.

From The Book In Progress…

The NamUs (National Missing and Unidentified Persons System) database, administered by the National Institute of Justice, is open for anyone to search. I use the system a lot, even train others to use it too, so I cracked my knuckles and entered the details I felt were pertinent. Namely, I was looking at the photograph of the girl in the truck on the basis it wasn’t Pamela Milliken and searching for unidentified bodies which matched up with Rhoades year-by-year driver’s logs from Empire Truck Lines. I set the criteria as: female, either white or American Indian/Alaskan Native, Adult pre-30, estimated year of death between 1984 and 1990, and found in Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Lousiana, Mississippi, or Alabama. I kept the timeframe, based on the facts of Rhoade’s truck routes, constrained to 1984 and 1987 to begin with, which gave me the selection of states. Of nearly fourteen thousand unidentified bodies listed in NaMus, the search returned only eight results and I felt a familiar flutter in my stomach: that instinct which says something might be there.

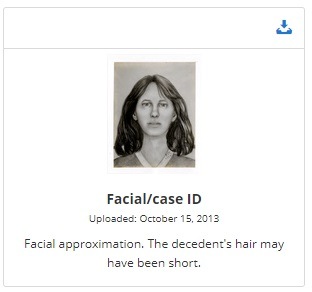

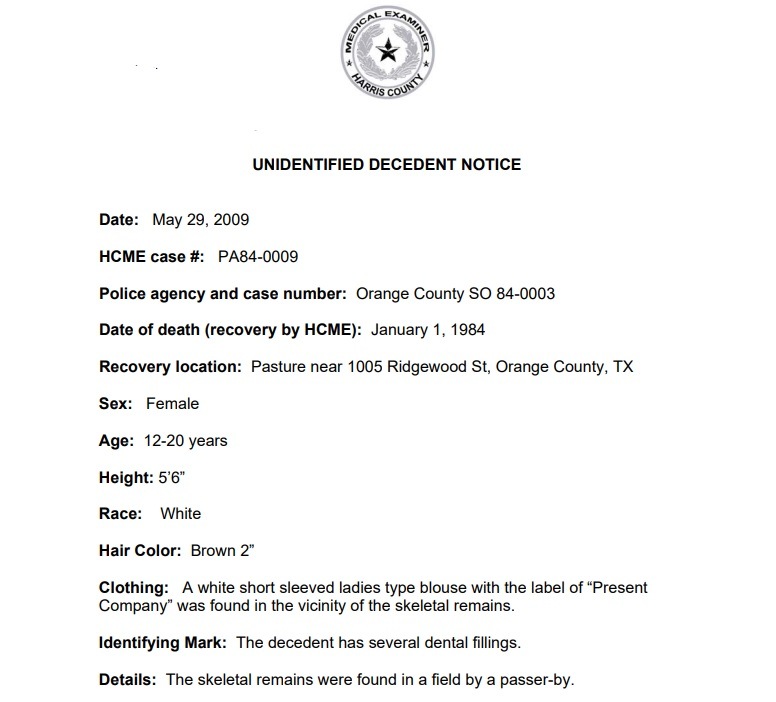

The first case was a female found in an abandoned building in a city location, which did not fit Rhoades’ pattern. The second and third were discounted too, for similar reasons. Number four was a different story. Case number PA87-061 was that of a dark-haired white female, aged twenty to twenty-one and found out in the sticks of Kingsbury, Guadalupe County on April 3 1987 – within spitting distance of the I-10 and only a couple of hours from Houston. It was close to Rhoades, I could feel that, but it still wasn’t him. The logs had him over in East Texas the whole time, driving between Dallas and Houston before heading into the neighbouring Eastern states. Number five was out for the same reason – too far West – number six was back to being an urban centre, and seven did not fit the truck route either. I was starting to wonder what had sparked my instincts when I clicked the last record, PA84-0009. The young girl in the composite sketch was about fourteen or fifteen by my reckoning, though the record expanded the age range to twelve to twenty. Not all of her body was intact in the field where she was found, near Vidor, Texas on the 1st of January 1984. In the sketch she had shoulder-length brown hair but then I saw it – the thing which was there to be found. Her hair had been cut, according to the records, and was no more than two inches long as if it were growing back from being shaved off. Rhoades cropped his victim’s hair. The location, near 1005 Ridgewood St, Vidor, was only yards from the I-10 and only fifteen minutes East of Beaumont. Rhoades dropped the bodies of his victims in secluded spots along his routes without going far off track. His 1984 driver logs took him directly along this route, but 1983 was another unfilled hole.

I shifted the search into missing persons, looking nationally for girls aged twelve to sixteen who had disappeared between October 1983 and December 31 that year. One case stood out, that of Sondra Kay Ramber – a brown-haired fourteen-year-old who disappeared from Santa Fe on October 26th. Details are slim and there’s some confusion between whether she vanished from home or while walking to school, so I decided to get in touch with the Institute of Forensic Sciences at Harris County who own the unidentified body case. I asked for whatever information they could provide on the deceased – the cause of death, and that mention of cropped or cut hair – and also to cross-check the records with Ramber’s missing person case, to see if the medical examiner had noted a mole on the right cheek during the autopsy. These things normally take a long time to resolve, especially when the case papers have been bundled off to the archives as was the case here. In the end, the wait was only a day and Harris County were amazingly helpful, sending across the autopsy report on the deceased girl as a PDF.

Joseph A. Jachimczyk M.D. was the forensic pathologist who conducted the autopsy for Harris County on the 21st April 1984. I knew straight away this meant the remains weren’t just partial, they were skeletal. Four months was too long a time between the discovery and the medical examination for any other explanation. It was confirmed in black and white, additionally stating the cause of death could not be determined. Helpfully, though, this did rule out the Ramber missing person case as being connected and the autopsy verified my thinking on why, stating death had occurred at least a year before. What little there was of the body arrived with the medical examiner in a carboard box, in what was noted as a “random array.” The reporting officers map showed the bones were spread out over quite a large area in the field. The poor girl’s remains were found in a pasture as a resident checked their fence-line after repair work. There was not much left of her – suspected to be due to animal predation – and the remains consisted of a skull but no mandible, some of the shoulders and ribs, and spine, most of the right arm but not the hand, and the left pelvis. Many of the teeth in the top half of the skull were missing – the front teeth noted as “post-mortem” absent, and the only anomaly found in X-ray were the fillings in teeth 13 and 14, meaning somebody had cared for the girl once, at least enough to take her to the dentist. A black nylon belt was found near the body, along with a green and white terry cloth Present Company blouse, and some matted red-brown hair which was about 2 inches long and noted as being fine.

It wasn’t a Rhoades case, just a badly worded NaMus record, but it was still a desperately sad tragedy. I adjusted the search criteria, shifting the date ranges, trying again and again with and without the description of the clothing. Looking for girls with braces on their front teeth. All that came up was a handful of improbable matches, which I eliminated one by one. I turned back to the description of the girl in the photograph which started all this and came up with no useful matches in the unidentified bodies which might provide an alternative identity to Pamela. Frustrated and left with nothing more to pursue -and no closure for the poor kid in the pasture – I eventually closed the browser and sat quietly for a while, gathering my thoughts. This stuff will haunt you if you don’t take the time to process it before carrying on with the work.

The accounts of the Rhoades case which exist are not what you would call forensics focused. In 1990, DNA was still in its infancy, having first been used to crack a murder in England in 1986 – the offender, Colin Pitchfork, has just been released after serving a thirty-three year sentence for the rape and murder of two fifteen-year old girls, causing disgust across the country. The uncle of victim Dawn Ashworth nailed public sentiment in mid-July 2021 when he told the BBC[1]: “It sends the message that child rapists, killers, murderers can at some point in time resume their lives when they themselves have deprived their victims of their lives.”

In America, the first outing for this new technology occurred in 1987, securing the conviction of rapist Tommie Lee Andrews in Florida[2]. It was prompted when Assistant District Attorney Jeffrey Ashton saw a magazine advert for paternity testing and wondered if it could be used to catch a man who raped a woman at knifepoint in her own home. Andrews covered his face and largely kept his fingerprints out of crime scenes, leaving the police flummoxed while twenty-two similar offences went on to take place between May 1986 and March 1987. It was not actually DNA alone which led to his capture though. He was careless at one scene, leaving two fingerprints on a window screen which could not be matched to any known records, but he eventually got caught by officers after a terrified woman reported a prowler. They ran his prints and matched him to the window screen crime, then used DNA to reinforce the prosecution case. We would still be in a much more chaotic situation now if the judge had bowed to the defence’s argument to exclude the DNA as it was “untested profiteering” by the testing company, Lifecodes Corp in New York. History was written in Florida that day in court. Andrews was tried repeatedly as new evidence was tested, his eventual sentence stretching to one hundred years.

At the very beginning, the sample sizes needed to perform DNA tests were much larger than today and the tests were less sensitive, using what is called restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP). Over the years things have changed significantly and the way crime scenes and individual items of evidence are processed has evolved – the cheaper and easier polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing being one example. New methods and technologies are being developed constantly, which led to me to a conversation with my Cold Case Foundation colleague Francine Bardole. Her background is fascinating.

“I attended the 10th set session at the body farm. I was very lucky to have Patricia Cornwell help pay for my attendance there, which was a ten-week training,” Francine told me. “It hit every area, and it was the most phenomenal training. I learned so much from that. Experts were all there and I still keep in touch with a lot of them. It was a wonderful, wonderful opportunity for me.”

Francine has worked in criminal justice for over twenty-five years now, carefully taking steps at every stage not to advance herself but to advance forensic analysis and the way victims are treated. She has pioneered her own technique for retrieving DNA evidence from small objects and shell casings – the Bardole Method – and is an experienced practitioner with the M-Vac collection system. The changes in the way DNA is handled over this time does not stop at PCR (a more costs effective and sensitive testing method), STRmix (software which can disentangle samples of mixed DNA from multiple persons), or any of the collection developments. Francine has been working at the forefront of a new DNA technique which is dramatically changing investigative practice and allowing those working these cases to step beyond the confines of the central Combined DNA Index System (CODIS).

“CODIS is what law enforcement the FBI and agencies use to try to make matches,” Francine said. “You enter a profile and you get someone’s DNA profile off of an item of evidence, and you don’t know who this person is so, you’ll put it into CODIS to see if it hits on anybody. I can tell you from my own experience, there have been some killers that have gone under the wire. There are those that never get in the database because, remember, we didn’t start really doing a lot of entering until later on, say early 90s and mid 90s. Also there were a lot of prisoners and people in prisons and jails that their DNA was not taken to put into that CODIS database. What we now have is genealogical profiling.”

I knew where she was headed and had used some of these services to fill in Rhoades’ background in Council Bluffs.

“If you think about Ancestry, Family Tree and 23andme,” Francine continued. “There’s different genealogical databases that people want to know who they are related to. There’s a lot of this information. Now that isn’t the same. That isn’t the same part of the DNA that we use to put in the CODIS database, the genealogical database uses what is called SNP or snips. You can’t reformat what’s in the CODIS database into a snip, it has to be done from the start, so snips are what they use in order to get your genealogical profiling – for example phenotyping. And what a phenotype is, it will tell you the hair colour, the eye colour, the skin colour. According to these snips are the probabilities of you having blue eyes – say it comes up with this person has a ninety-six percent chance of having blue eyes, and brown hair? Maybe an eighty-five percent. We can get an idea of physical characteristics from this phenotyping, which can really help if you’re getting the person in as soon as possible.”

The question which dances around new developments like this, is always: does it have a practical use? The answer is yes, in this case. And it has already landed big fish in the under the radar serial killer world.

“One would be the Golden State killer, out of California,” Francine said.

The Golden State Killer, Joseph James Dangelo – a former police officer – committed thirteen confirmed murders, fifty rapes, and one-hundred-and-twenty burglaries from 1973 to 1986. He was only identified and finally captured in 2018, in his seventies. The genealogy records of a relative were tied to DNA collected from his crimes – which had, until then, sat unmatched in CODIS for years.

“He started out raping, then he ended up killing and he went free for a long time, until they were able to put it into GEDmatch,” Francine explained. “That matches the genealogical databases where they were able to find out closest relative so you can move into the direction of where this person would probably be and who they’re related to. This is very valuable. I know there’s a lot of kickback with people not wanting their DNA in a database or being able to be searched but, in my estimation, if you’re not guilty, there really shouldn’t be an issue with it. I would rather see a killer off the road or off the street or out of my community than attack somebody I care about or love. A child, a parent, a brother, whoever. This will really help in that situation. I do believe, in the future this is the direction things are going to go.”

Thinking about an expanded DNA database, I imagined how different the story of the girl in the pasture would be. She would never have become an anonymous kid. An unidentified body scattered by animals and left incomplete. Who she was would be known. Her family would be known. More than likely her killer would be known. The sheer volume of cold cases would be reduced in a stroke by eliminating one of the greatest opportunities which exists in America: the ability to cross state and county lines and be unknown. One little pin prick at birth could change the shape of crime in America forever, and change the destiny of little children who never even grow old enough to appreciate the concept that some people regard human life as disposable. There wouldn’t be fourteen thousand unidentified bodies listed on NaMus.

This is a huge issue, though. Well beyond my personal capacity to even know where to start, so I let the thought burn down and poked the embers of the rest of my conversation with Francine. Sat in an evidence locker somewhere, unless it has been thrown away or destroyed, or rusting in a junk yard inside an old International truck and an unknown, alternative rig, sits the evidence she could use to light up Rhoades’ true offending history.

Context Matters

This truly is a complex and, for many, controversial topic area, set against a backdrop of global differences in approach to fundamental rights and freedoms which can make discussions like this too hot to touch. Nonetheless, there are still these much bigger discussions to be had around the way we use the power of DNA to prevent harm in society and that’s the real challenge here – getting to a point where the basic premise of the discussion is understood in its simplest form: a problem to solve. For me the conversation starts with that poor girl in the field. She deserves to be known. She deserves peace. In a world where her DNA was attributable to her, nearly forty years wouldn’t have passed. But sometimes solving one problem can create many more conflicts and it is important to appreciate that fully.

This is the thing about investigative work. Sometimes, there’s just no easy answer. But we still have to talk about even the things we might not want to, calmly and rationally, because an unexplored avenue might be the one where the right answer lies.

The Rhoades case is providing me more food for thought than I ever imagined it could.

[1] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-leicestershire-57737050, Colin Pitchfork: Double child killer’s release confirmed, BBC Local News, July 13 2021

[2] https://www.police1.com/police-products/investigation/dna-forensics/articles/police-history-how-a-magazine-ad-helped-convict-a-rapist-wEnPKjpf6S3brBpF/, Police history: How a magazine ad helped convict a rapist, Police 1, August 28 2018

If you are not already a member, join Cold Case Live today to directly support the ongoing casework of the Cold Case Foundation and to help us develop this vital resource in the fight against serious crime.

Responses