Finding Patterns in Data

James Patrick, Director of Socint | Investigator at the Cold Case Foundation

Finding patterns in data does not have to be overcomplicated or treated as a deeply technical exercise only accessible to data scientists. A slow-time approach, while highly valuable, can cost lives and should be conducted in tandem with real-time analysis.

Vast volumes of data are available to police forces and some of that data has entered the public domain. We have been using that data as we continue to develop the Themis project – a game-changing system which will facilitate a greater understanding of cross-jurisdiction crime, make better technology available to police forces of all sizes, and facilitate direct public assistance with investigations in a structured and auditable way.

While those developments continue, it’s important that we continue our work to educate and inform officers and the public – sharing the knowledge and expertise to help reduce crime and uncover serial patterns, and hopefully make complicated topics like data analysis more accessible to all.

I really wanted to take the time in this article to show how publicly available electronic information (PAEI) can be used in a practical way to quickly sift through large amounts of information and guide problem-solving efforts or investigative research.

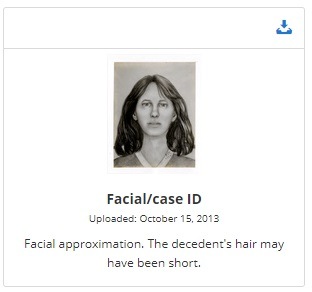

Unidentified Persons

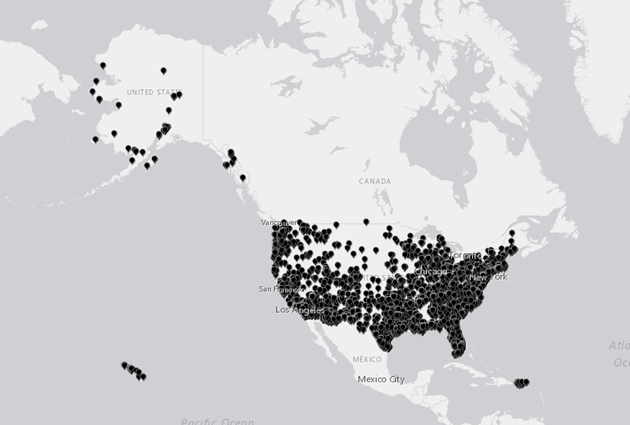

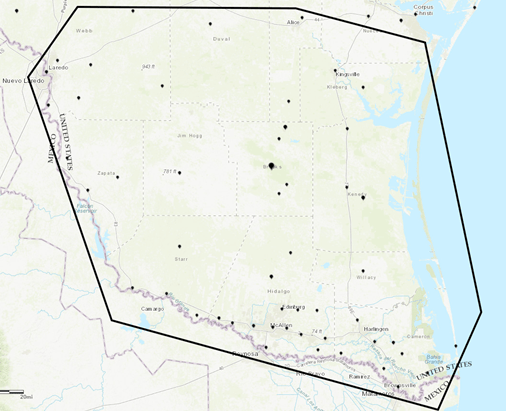

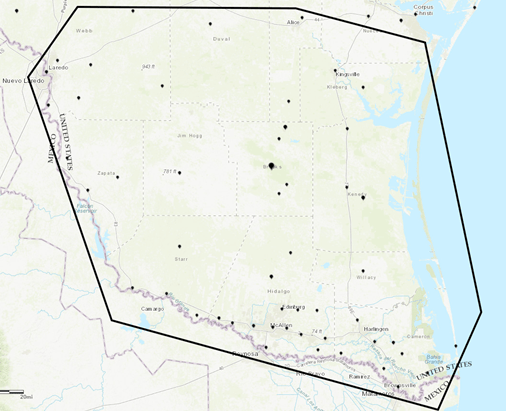

The NAMUS database holds thousands of active missing person cases and thousands of unidentified persons cases too. Placing 12,840 unidentified person cases on a map of the United States shows a huge spread of mapped-points, but we need to rationalise this data to help us identify problems and anomalies.

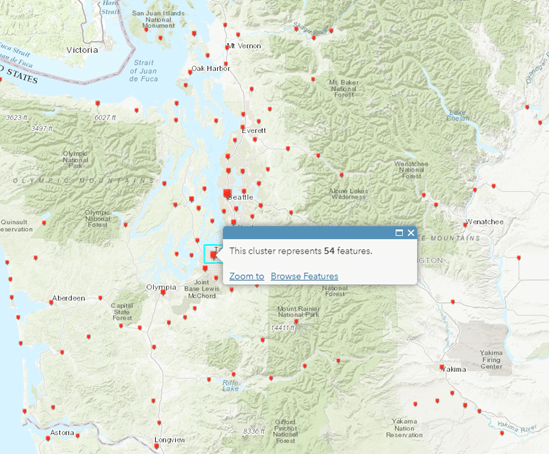

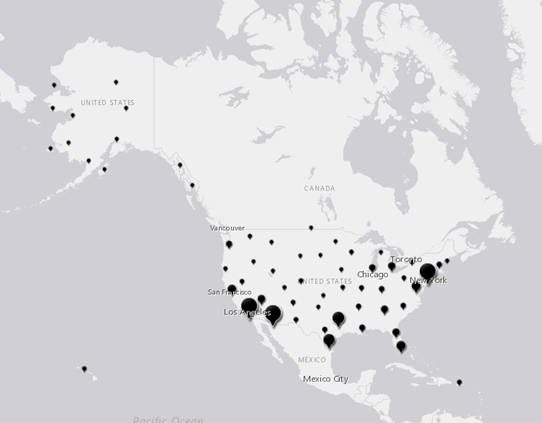

Using ESRI’s ARCGIS Online mapping system, it’s easy to apply a cluster filter to mapped data, which reduces the signal noise and allows quick visualisation of the places with higher cases volumes.

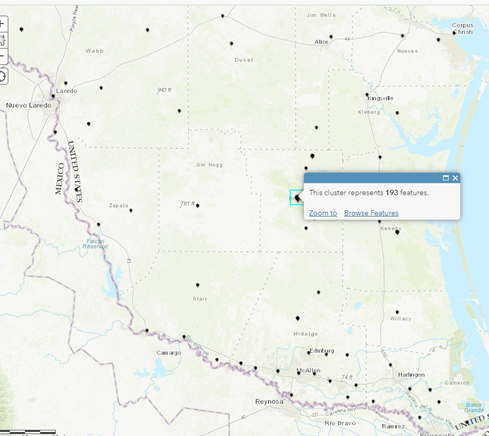

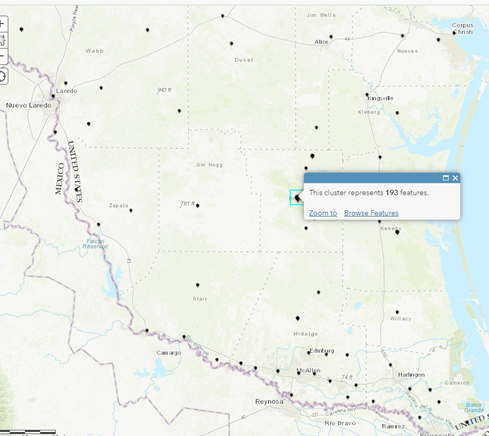

Selecting a random cluster with a higher number of cases, Texas provides a good example of how these geographical visualisations can identify patterns.

Even at a glance, you can immediately discern a link between unidentified persons cases and, sadly, deaths occurring in the proximity of the US-Mexico border crossing routes, as well as a significant deviation from the norm in Brooks County – where 193 cases are clustered on a single location.

Simply clustering data and identifying a deviation from norms meant that research could be focused on a single term “Brooks County Unidentified Bodies.”

Within minutes of a blind data analysis of tens of thousands of cases, it was possible to find records detailing that the county-run Sacred Heart cemetery, Fulfarrias, Brooks County was exhumed in 2014 by a research team from Baylor University who found mass graves of skeletons, bodies dumped in trash bags and milk crates, or scattered in the dirt of open graves.

Missing Persons

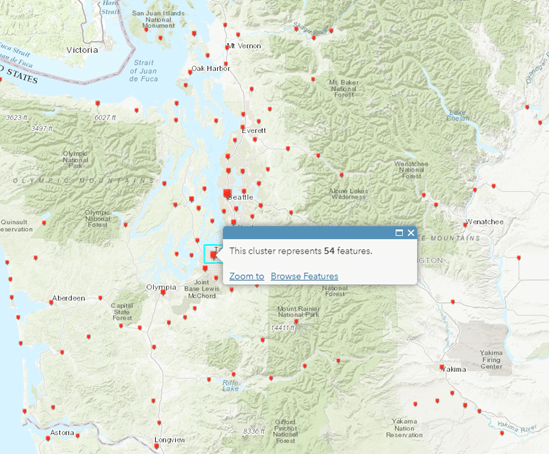

Applying the same clustering to 19,646 active missing person cases across the United States produced a similar result, allowing us to zoom in on one area as an example. Tacoma in Washington State stood out for potential analysis, as a smaller metropolitan centre with an elevated case load.

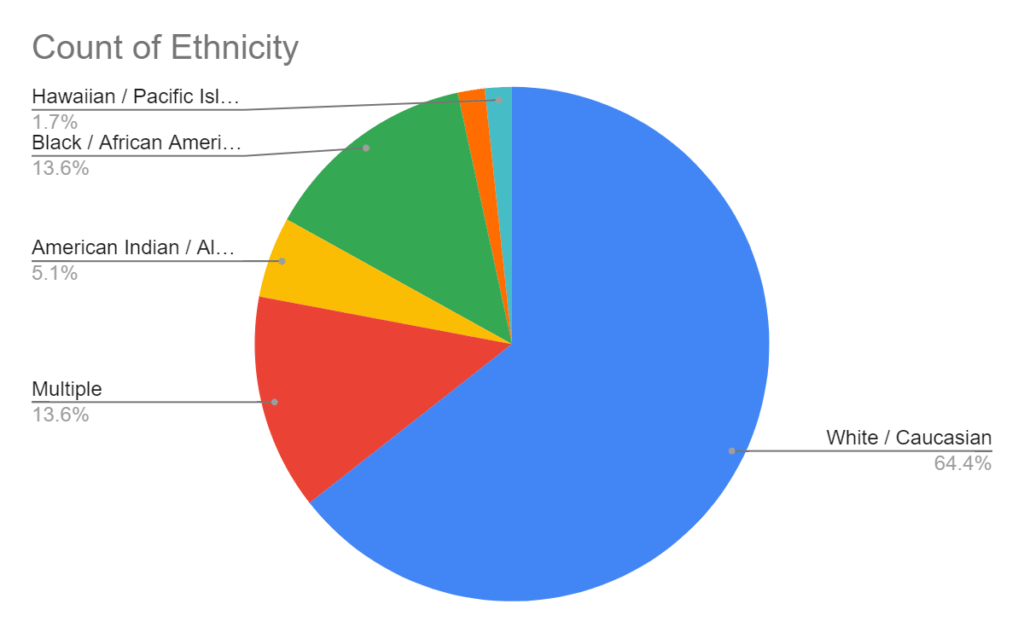

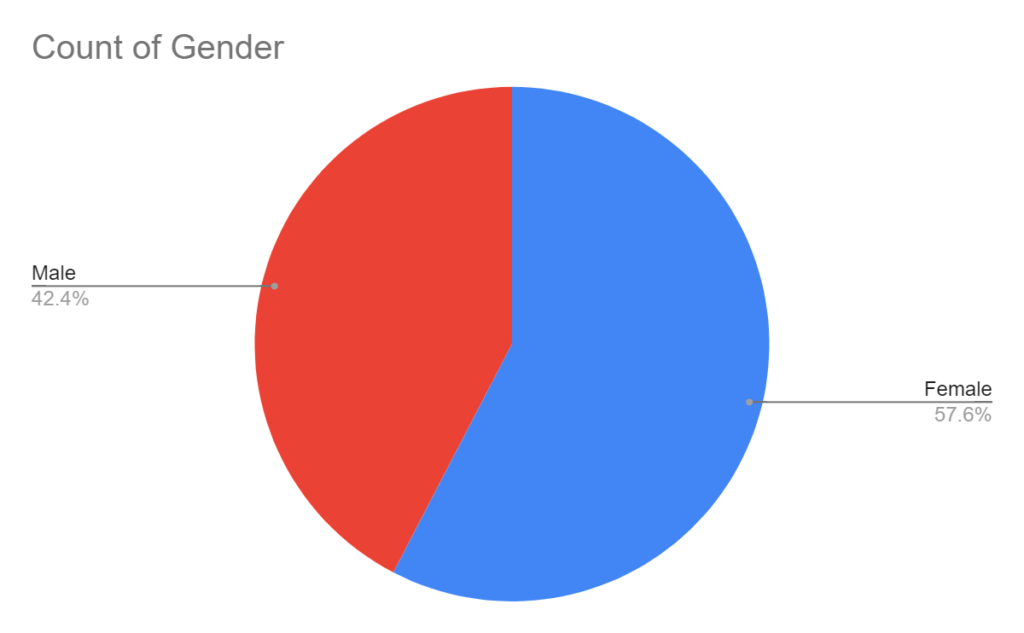

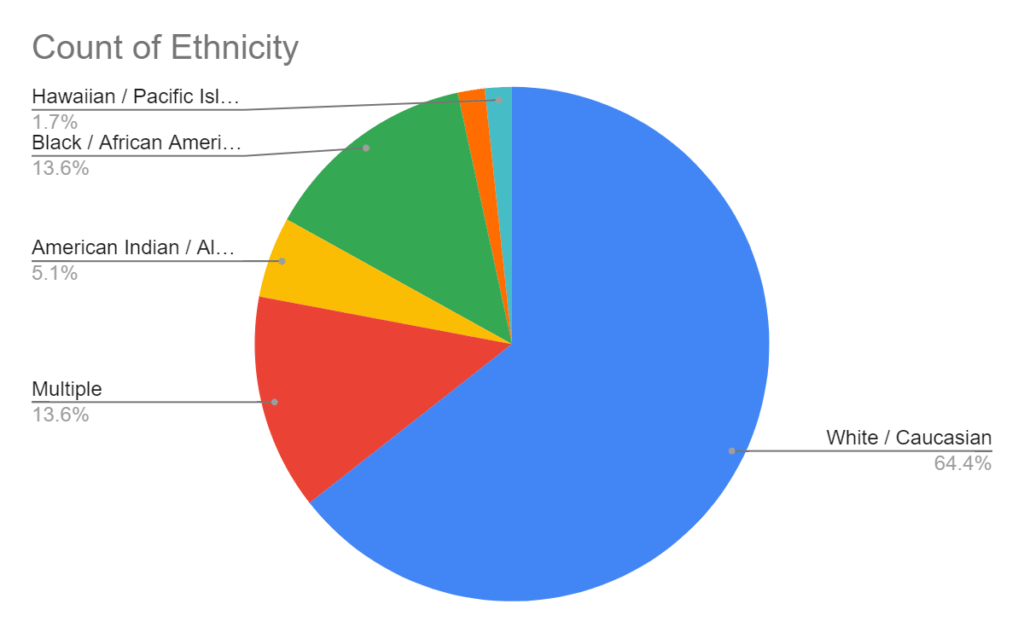

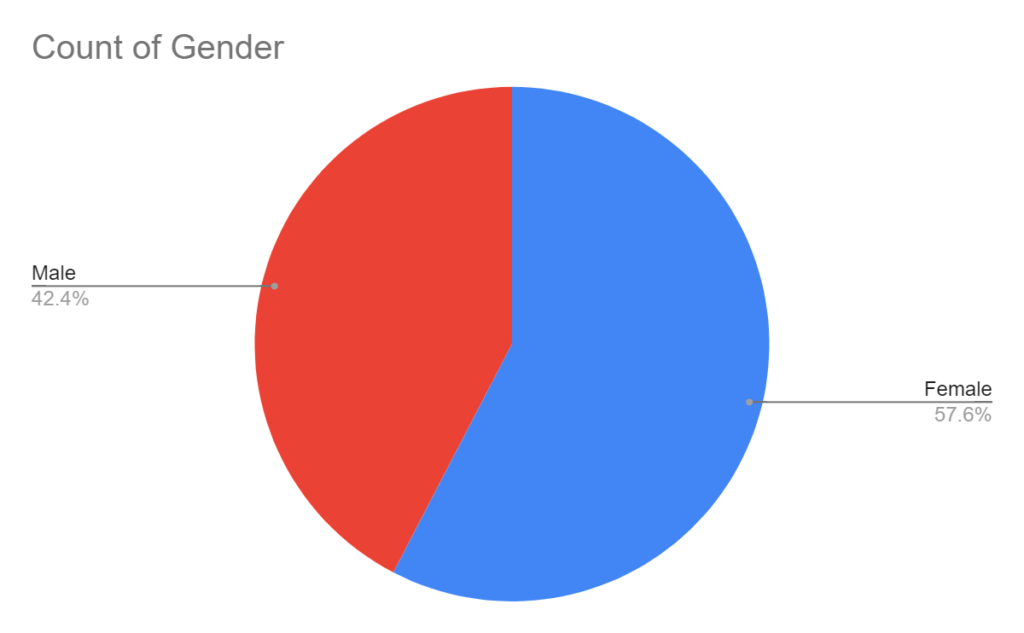

Extracting the Tacoma case data from the visualisation, headline analysis of missing person characteristics showed that the vast majority of cases where white (64.4% of the total) females (57.6% of the total).

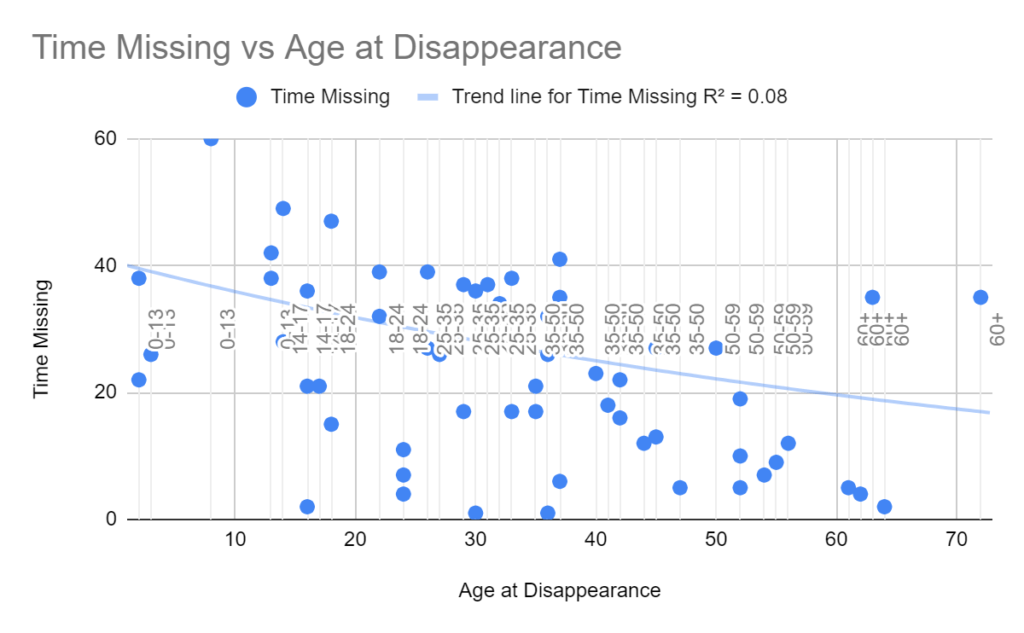

Calculating the time missing and then plotting the unsolved case’s open time against the disappearance age of the missing person gave an indication that the younger a person was when they went missing, the longer they would remain missing with a case open.

There is, of course, case-by-case nuance to be applied to this result so it should only ever be noted with caution, rather than be used to define a rigid case characteristic.

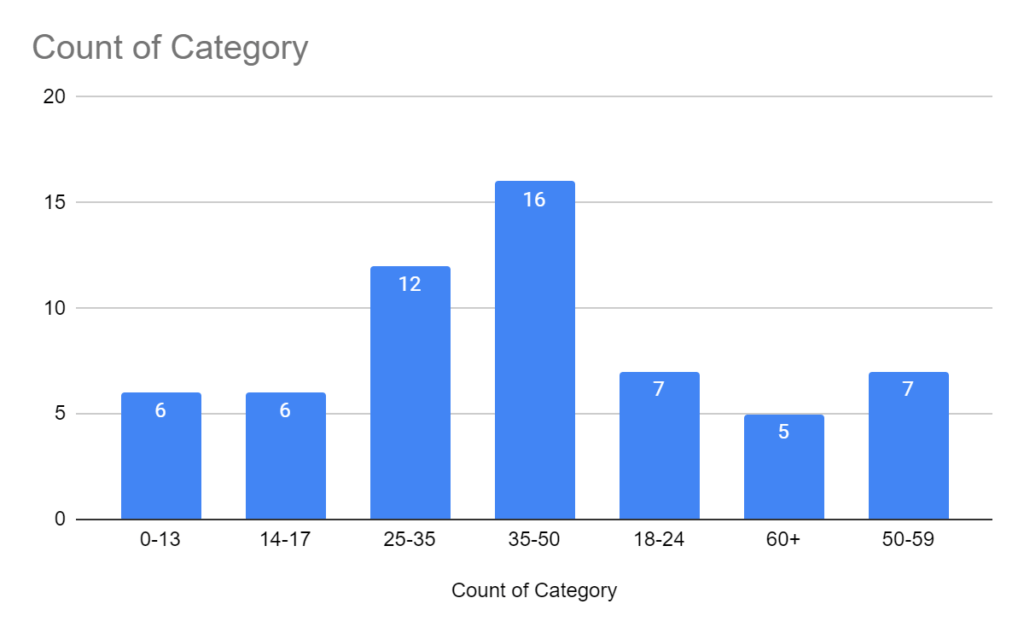

The cases were then categorised by age grouping to identify any clear patterns in missing person characteristics in the Tacoma area.

It’s clear in the data that most unsolved missing persons cases in the area relate to people aged 25-50.

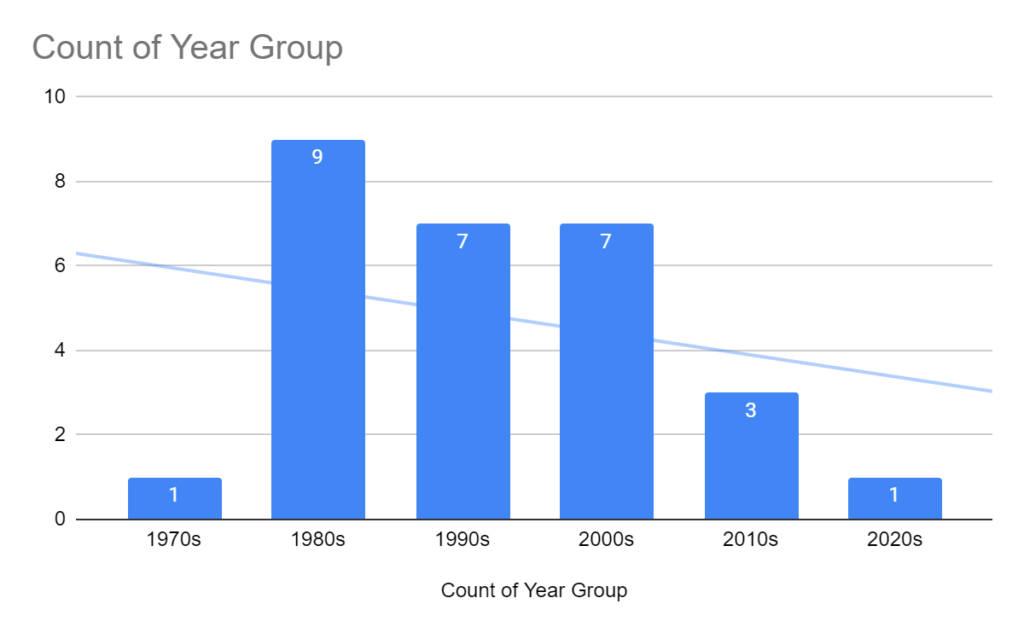

Focusing on the 28 cases with missing persons aged between 25-50, the dates of the disappearances where categorised by decade to help identify any potential patterns.

The 1980s clearly stood out.

Of those 9 Tacoma missing person cases in the 1980s, the vast majority were women (77.8% of the total) from white ethnic backgrounds (71.4% of the total).

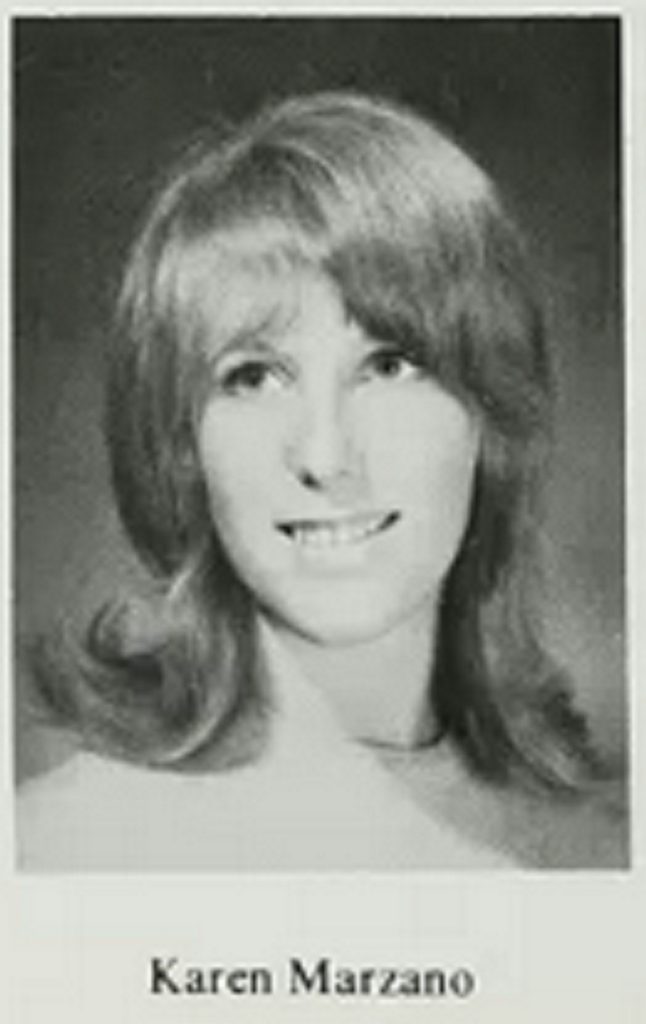

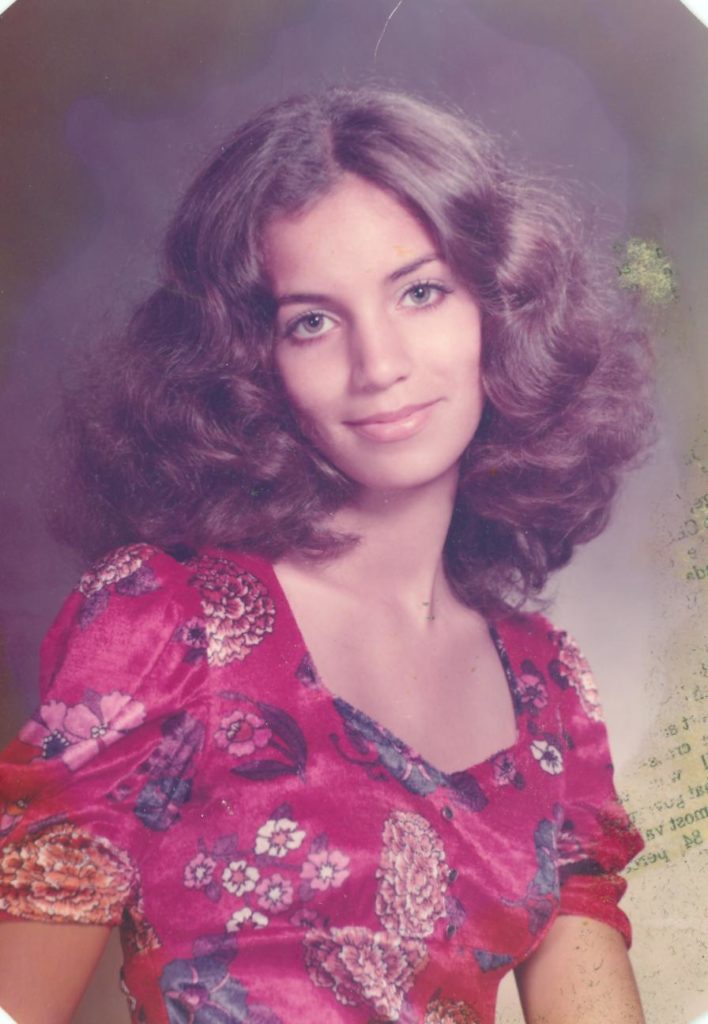

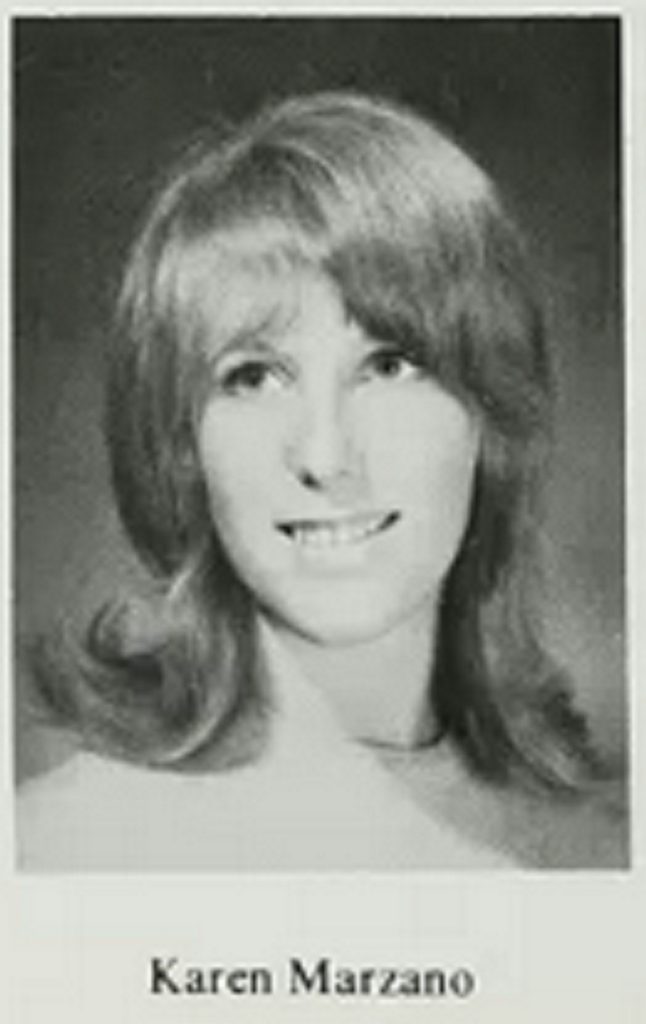

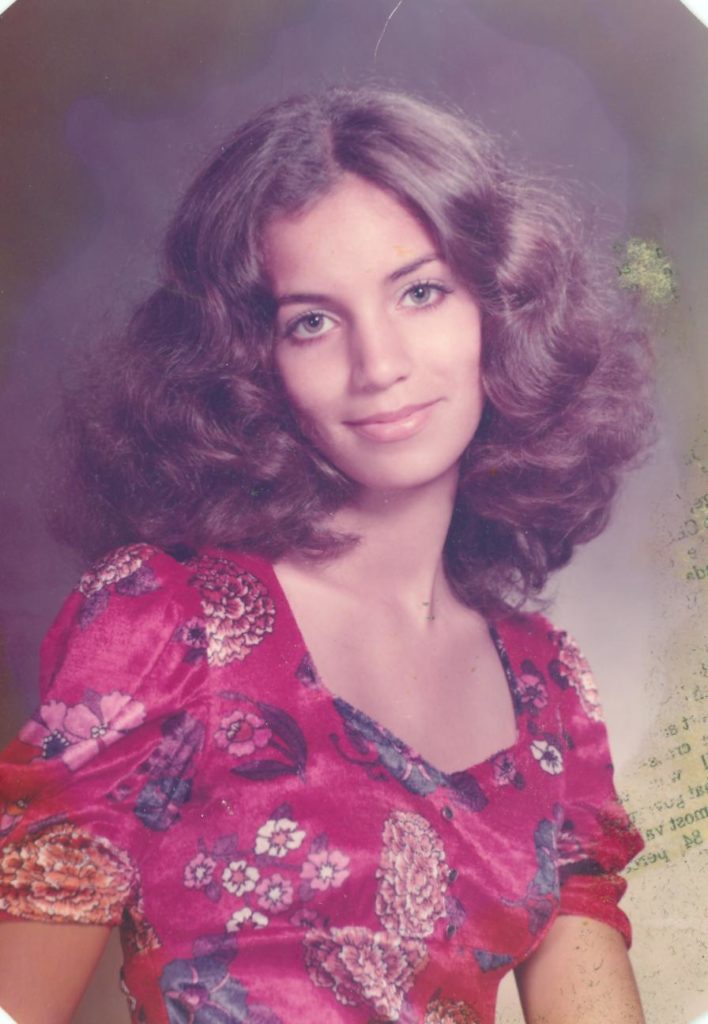

The cases of four of these women stand out as potentially being part of an identifiable pattern: Karen Penson (Aged 31, vanished May 1983), Maria Colon-Seda (29, vanished July 1984 ), Patricia Colyer (37, vanished July 1986), and Margaret Diaz (32, vanished July 1988).

Penson is now suspected to have been the victim of foul-play at the hands of her then husband.

During the time these women went missing, notorious serial killer Gary Ridgway was active in the correct geographical area, though there is no indication he is linked to these cases and the victim profile is varied from Ridgway.

It is worth noting, however, that if we apply a “Ridgway filter” to cases in Tacoma, the analytical process immediately identifies Debra King – who disappeared in July 1982 and has long been listed as a potential victim of Ridgway.

Interestingly, King, Colon-Seda, Colyer, and Diaz all disappeared in the month of July.

Conclusion:

Using only PAEI, it is possible to quickly identify unusual case clusters which directly connect to real-world events and timelines. This can significantly accelerate research and investigation.

Creating offender specific filters is also a fast-time action which can pay dividends in any complex investigation, without the need to write and deploy complex, automated algorithms.

When applied to internal police data, the case details which are not made public, cluster analysis can be the difference between life and death.

James Patrick is an intelligence specialist who served as a police officer for a decade. On leaving Scotland Yard he was commended by the British Parliament. He now focuses on threat mitigation and intelligence analysis, specialising in the digital and information landscapes.

If you are not already a member, join Cold Case Live today to directly support the ongoing casework of the Cold Case Foundation and to help us develop this vital resource in the fight against serious crime.

Hi, Do you have experience using Maltego Open Source Intel software ? It is very powerful and has ways of mining and transforming personal data that would make your hair curl. It’s something I have yet to learn how to use, but from what I can gather so far, it could be a useful tool to help the CCF gather intel.

If you are not familiar with it, here is one of it’s many capability’s.

https://youtu.be/D2rutsb-ft0

Hi Michael,

James here. Have used Maltego quite a lot over the years. It is a very good tool and the community edition is excellent.

Over that same period of years, having deployed a few different tools – I2, etc – I’ve actually ended up developing my own system and some virtual machines for OSINT trainees.

Over the next few months there’ll be lots of exciting news on this.

Best.

[…] administered by the National Institute of Justice, is open for anyone to search. I use the system a lot, even train others to use it too, so I cracked my knuckles and entered the details I felt were […]